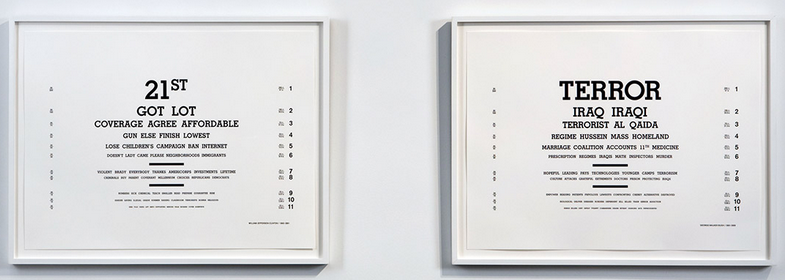

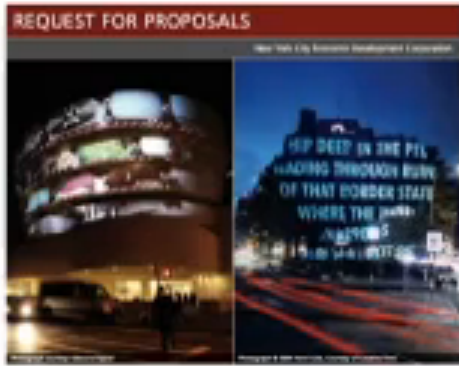

"Today, with big data and its implications so important to citizenship and society, artists are at the forefront of helping us see and understand data in altogether new ways. And the questions they ask help us process our collective anxiety and fascination with the phenomena of a pervasively instrumented world."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed